“America is my country, and Paris is my home town.” – Gertrude Stein

“Paris has always seemed . . . the only city where you can live and express yourself as you please.” – Natalie Clifford Barney

A few years ago, my husband and I were visiting one of Europe’s major modern art museums for the first time (a museum that shall remain nameless), and the temporary exhibition was dedicated to one our favorite topics – “Modernist Paris.” It was an impressively large exhibit, housing dozens of paintings, drawings and sculptures over several large rooms. Plenty of space to move about. It didn’t feel crowded. But. To our disappointment, this outstanding venue had been filled with the same old artists we’d seen a hundred times before in every other European and North American modern art museum. All the usual suspects were there: Picasso and Braque, Matisse and Modigliani, Kandinsky and Maillol, Max Ernst and Fernand Léger. All men, all white, all European, all (presumably) straight (or at the very least not openly queer). Don’t get me wrong. We’re not attacking the quality of their work, or saying that their work shouldn’t be displayed and enjoyed, studied in schools, included in textbooks, etc. But after years and years of seeing every inch of every major art venue dedicated to the same few “big” names, repeated ad nauseam . . . it’s getting boring. We’re bored. We want to see something new, a different perspective, someone we’ve never seen in a museum before. We know for a fact that there is an abundance of *amazing* modernist art out there, by a vast array of diverse voices. And a significant amount of this art also happened to be created in Paris during the modernist era.

At the exhibition in question, we remember being *shocked* that there wasn’t a single work by a woman artist. Not even one! And yet the exhibit contained plenty of nude women portrayed in the paintings and sculptures. The famous question of the Guerrilla Girls (“Do women have to be naked to get into the Met. Museum?”) certainly applied here. Nude women are fine, as long as they are painted or sculpted by the usual suspects. But no women artists allowed! And not one work by a person of color, a non-European artist, or an openly LGBTQ+ artist. To the average museum-goer, one might think that art created by these marginalized groups doesn’t exist, isn’t important, or just isn’t very good. Or maybe there are artists now with those identities, but definitely not back then, because we all know what those times were like. It couldn’t have been easy for women artists or Black artists or trans artists to have a career in Paris at that time. They must not have existed. But this is patently false. And historically inaccurate. Because Paris in the 1910s, 1920s, 1930s, 1940s and 1950s (and the 1960s and 1970s . . .) was an extremely diverse place, attracting artists from all over the world. Amazing artists. Insane amounts of talent. Geniuses and prodigies. And, as is true of every other time and place in art history, not all of those geniuses were straight white men from Europe.

I. Sisters Are Doing It for Themselves

“I didn't have time to be anyone's muse . . . I was too busy rebelling against my family and learning to be an artist.” – Leonora Carrington

“All Picasso's portraits of me are lies. They're all Picassos. Not one is Dora Maar." – Dora Maar

“I love creation more than life, and I must express myself before disappearing.” – Sonia Delaunay

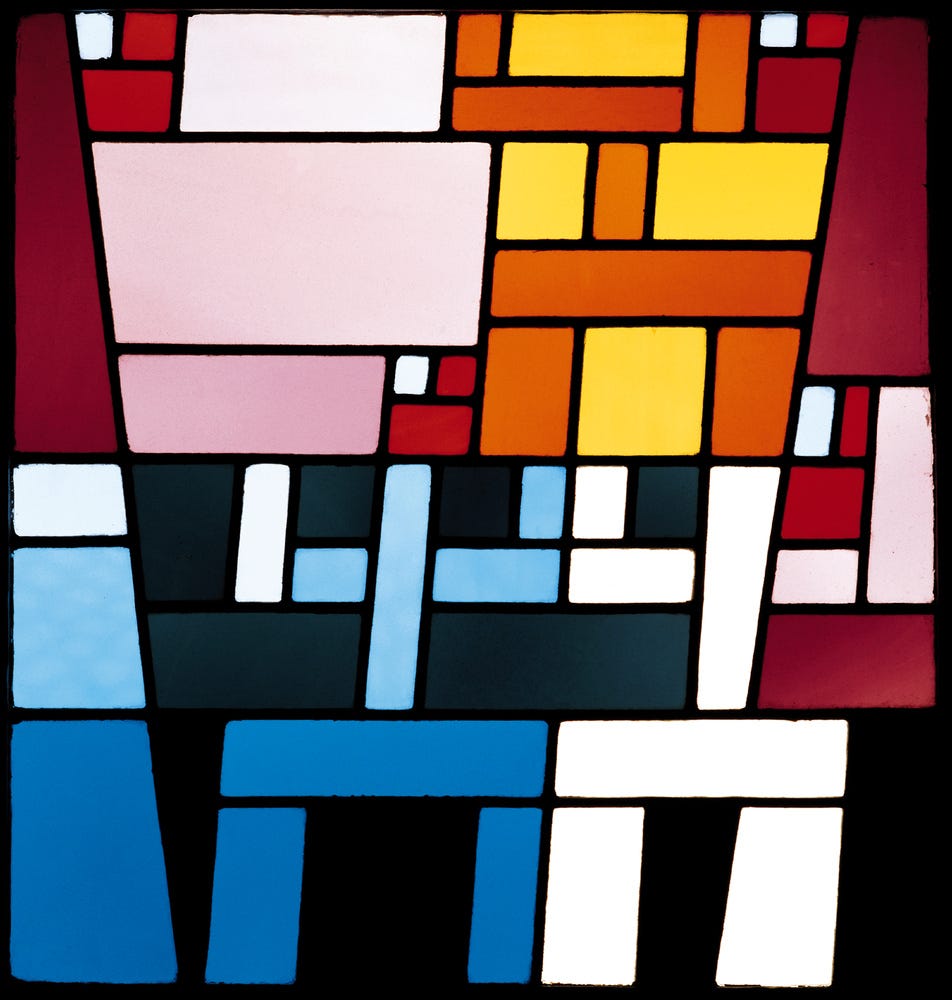

First let’s talk about the women artists. Sonia Delaunay, for example, whose work is often paired with her husband Robert (or ignored entirely), actually had a much longer, productive, and prolific career. Robert died in 1941. Sonia, however, lived until 1979 and thus had a 75-year-long (!) professional career as a working artist. Born to Jewish parents in Odessa, Ukraine, she moved to Paris in 1905, where she then resided for the rest of her life. Her bold canvases, bursting with color, often in the form of juxtaposed circles, not only prefigure the rise of abstract expressionism, but were later incorporated by Delaunay into her elegant designs for textiles, fashion, interior furnishings, costumes, theatre and ballet sets, dinner plates – even a car! A comprehensive solo exhibit of her work some years ago at the Centre Pompidou in Paris was another highlight in our museum memories. Thankfully the Pompidou’s recent revamp of their modernist art collection (on permanent display) has returned Sonia Delaunay to the center stage where she belongs.

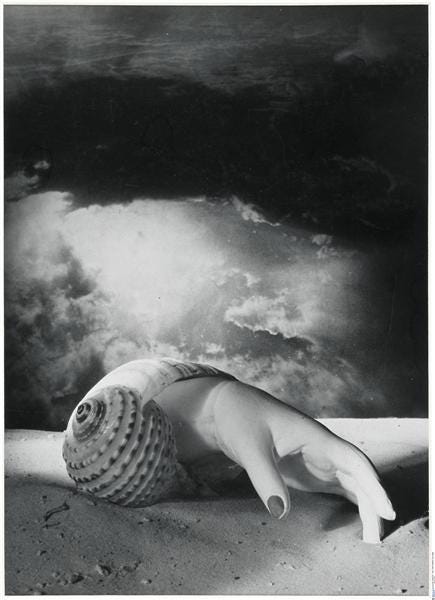

The gatekeepers of art history have spent decades trying to systematically ensure that many other women artists were overshadowed by their husbands and male partners. Dora Maar is primarily known as the muse, model and lover of Picasso from 1935 to 1943, and the subject of some of his best-known works. However, she was also a painter in her own right, and her striking photography and transgressive photo-collages are valuable on their own merits. Likewise, Dorothea Tanning’s brilliant surrealist paintings are just as interesting as those of her husband, Max Ernst (1891-1976), and yet his work is regularly on display in museums while her work is rarely seen. Even though Tanning lived (and painted, and wrote poetry) until the age of 101 in 2012! The story of Ernst’s earlier lover, the iconic painter Leonora Carrington, whose parents committed her to an asylum after her break with Ernst, then had her released and sent to yet another asylum in South Africa, only for her to bravely escape this fate by marrying the Mexican ambassador (a friend of Picasso) and gaining diplomatic immunity, then emigrating to Mexico and relaunching her artistic career . . . just might be beyond the scope of this essay. Though she lived and worked in Paris too!

Sophie Taeuber-Arp, the Swiss painter, sculptor, textile artist, interior designer, and architect, despite her significant contributions to abstract expressionism, is likewise often overlooked in favor of her husband Jean Arp. Russian émigré and multitalented artist Natalia Goncharova’s lifelong partner was fellow émigré-painter, Mikhail Larionov. Guess which one gets all the credit for inventing Russian Futurism? Even one of the most iconic works of modernism, Marcel Duchamp’s readymade “Fountain,” was likely found/created (and signed) by none other than the “Mother of Dada,” aka the Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven. Don’t take my word for it. Here’s what Duchamp himself said in a letter to his sister: “One of my female friends under a masculine pseudonym, Richard Mutt, sent in a porcelain urinal as a sculpture.” The self-appointed Baroness, by the way, had already been using found objects to make readymade assemblages and even Dadaist costumes for many years prior to Duchamp.

And let’s not forget the trailblazing Suzanne Valadon. Valadon, too, is known as a model for Renoir, a friend of Degas, a lover of composer Erik Satie, and the mother of painter Maurice Utrillo (one of the famous artists of Montmartre). But Suzanne Valadon was so much more than the various men in her life. I still remember attending the Pompidou’s traveling exhibition, Elles: Women Artists from the Centre Pompidou, Paris when it reached the Seattle Art Museum in 2012. I went with my mom, a devoted Valadon enthusiast (I think she’s read every Valadon biography), and even she wasn’t prepared for the full impact of seeing Valadon’s The Blue Room (La chambre bleue), from 1923. This self-portrait on a relatively large canvas, revealing a plus-sized woman, wearing baggy striped pants and a loose-fitting top, reclining in a comfortable position on her bed, smoking a cigarette and surrounded by books, is perhaps the supreme image of the liberated, intellectual, modernist woman artist. Self-assured, independent, confident, not trying to impress anyone else. Suzanne Valadon needs a man like a fish needs a bicycle.

II. No Modernism Without Lesbians

“I live life in the margins of society, and the rules of normal society don't apply to those who live on the fringe.” – Tamara de Lempicka

“My queerness is not a vice, is not deliberate, and harms no one.” – Natalie Clifford Barney

“Why should I paint dead fish, onions and beer glasses? Girls are so much prettier.” – Marie Laurencin

Many groundbreaking modernist artists were also lesbians, bisexual (or pansexual) women, or otherwise queer and gender non-conforming. Check out Shari Benstock’s Women of the Left Bank: Paris, 1900-1940, which was also turned into a great documentary, Paris Was a Woman (1996), directed by Greta Schiller. I also strongly recommend Diana Souhami’s No Modernism Without Lesbians. These books and documentary reveal an entire subculture of (mostly) queer women artists and writers who were thriving in Paris at the height of modernism. Gertrude Stein alone was one of the most significant patrons and catalysts for modernist art as we know it. In addition to her friendships with Picasso and Matisse, which included being an enthusiastic early patron/purchaser of their work, she also actively promoted their art, championed their aesthetic choices, and provided a crucial place of networking via her well-connected salon. But the Parisian salons of the Left Bank, primarily led by women, did not exist solely to promote the work of their male colleagues. And while the major salons were indeed led by women writers like Stein, Natalie Barney, and Edith Wharton, and frequented by writers and publishers (like H.D., Bryher, Mina Loy, Djuna Barnes, Colette, Janet Flanner, Jean Rhys, Sylvia Beach and Nancy Cunard) many of the female attendees of these salons were also amazing visual artists.

In fact, these women-led salons helped initiate a thriving tradition of female-centric modernist art. In addition to mentoring, supporting and providing a communal space for many of the heterosexual women artists listed in the previous section, it is astonishing how much artwork was being created in Paris by queer women artists. Let’s just examine a few regulars at Natalie Barney’s woman-only salon, which she based on a mythical reconstruction of the ancient school of Sappho of Lesbos (Barney herself once said that modernist Paris was the “the Sapphic Centre of the Western World”). First we have Romaine Brooks, who was Natalie Barney’s romantic partner for over 50 years. Her striking portraits of strong, eccentric women include La Baronne Emile D’Erlanger, with her black cape and striking red hair, eyes fixed on the viewer, as she appears to be letting a rather enormous feline out of a cage. Or Una, Lady Troubridge, the lover of novelist Radclyffe Hall, clad in a monocle and a dapper man’s suit, smirking as she strokes her pair of dachshunds. And then there’s Peter (A Young English Girl), a portrait of the British painter Gluck, who wore men’s clothes, rejected gender pronouns and prefixes (like Miss or Mr.) and who was certainly gender-nonconforming and/or non-binary by today’s standards.

Among Natalie Barney’s other salon regulars, we find Marie Laurencin, with her lush pastels of stylish, gossamer-clad women in a distinctly modernist style, who seem to inhabit a luminous and ethereal Otherworld. Also Berenice Abbott, formerly an assistant to Man Ray, who forged her own career with her haunting urban photography and striking photo-portraits of fellow artists and intellectuals like Jean Cocteau, James Joyce, Janet Flanner and Djuna Barnes. And the outrageous Tamara de Lempicka (“The Baroness with a Brush”), a Polish artist infamous for her countless scandalous affairs with all genders, but who is hopefully more appreciated for her glossy, luscious art deco portraits of aristocrats, jet-setters, and “Bright Young Things” stumbling from one cocktail party to the next. It is no coincidence that all four of these women had romantic relationships with other women. Their portrayals of female and feminine beauty, from a queer woman’s perspective, manage to simultaneously subvert the male gaze, affirm their own homoerotic desire, and offer a fascinating and much-needed counterpoint to their heterosexual male contemporaries.

Above: The Green Turban by Tamara de Lempicka (1930) [© Tamara de Lempicka Estate LLC]

And that’s the end of part one. Hopefully this first part gives a glimpse of the many diverse voices that remain to be explored in this fascinating era. In part two, we’ll take a look at the many incredible Black artists (both men and women) who were living, working and creating outstanding art in modernist Paris!

Recommended Reading:

Thanks for this! I love seeing all of these artists here. I was startled to see the Dora Maar book, as it seemed familiar, then remembered I wrote a review of it back in 2017! Highly recommended. http://www.fractionmagazine.com/dora-maar

A wonderful article. It brings back memories of the many great paintings by female artists that I was able to see in person at museums & exhibits during my trips to Paris.